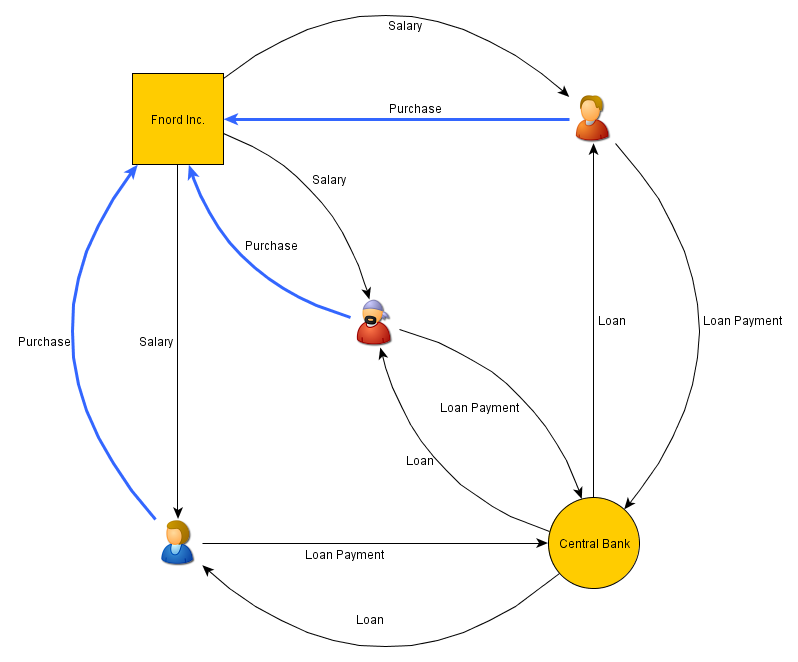

Continuing on the idea from the previous entry, we will track through what should theoretically happen when exchange system is used when money appears to deflate due to a decreased velocity of money. To make life easy, we will use the below model of the macro economy, rather than the rather complex (and still incomplete) image included in the previous blog:

We’ll say that we have three citizens of our economy, Jack, Alan, and Tina. Each month they spend $800 on food, clothes, gas, electricity, etc. which they purchase from Fnord Inc. They are also all in debt to the central bank, owing $50 each month to pay back a $500 loan. Their salary is $1000 per month working for Fnord Inc.

| Balance Sheet | ||||||

| Month | Apparent Money (per month) | Debt | Fnord Inc. | Jack | Alan | Tina |

| Initial | $3000 | -$1500 | $3000 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

Unlike the modern world where the salary is pegged to a particular value, in the new system of doing things the salary is based on the value of the Apparent Money (AM) as it has tracked from month to month. We calculate the AM by adding all purchases. The initial value is set to $3000 as we assume that if Fnord Inc. is able to hire 3 people for $1000 each, they must have received $3000 in the previous month. Besides adjusting salary, we also adjust the amount of our loan payments — and in fact the total amount of debt as well.

In the first month, Jack, Alan, and Tina are each paid $1000. They purchase $800 worth of supplies, pay $50 in loan payments, and save the remaining $150. The total of all purchases in the economy for this month was only $2400, so we update the Apparent Money to that.

| Balance Sheet | ||||||

| Month | Apparent Money (per month) | Debt | Fnord Inc. | Jack | Alan | Tina |

| Initial | $3000 | -$1500 | $3000 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 1 | $2400 | -$1350 | $2400 | $150 | $150 | $150 |

With an AM that is 80% of the previous month, Fnord adjusts the amount of salaries to match and pays its three employees $800, which is the same as their $1000 salary at current apparent inflationary/deflationary rates. At the current AM, the amount that is owed in debt is reduced to $1080 ($360 per person) and the amount owed is lowered to $40. Knowing that the amount of money in the economy has decreased, Fnord Inc. also lowers the price of all of its products by 80% and so our three citizens end up buying their usual goods for only $640 each, paying the $40 in loan payments, and save the remaining $120.

| Balance Sheet | ||||||

| Month | Apparent Money (per month) | Debt | Fnord Inc. | Jack | Alan | Tina |

| Initial | $3000 | -$1500 | $3000 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 1 | $2400 | -$1350 | $2400 | $150 | $150 | $150 |

| 2 | $1920 | -$960 | $1920 | $270 | $270 | $270 |

Heading into the 3rd month, it’s worth pointing out that the $270 in our citizens’ savings is worth $421.88 at the value of money at Initial. They have made only two deposits, having expected to have saved $150 each month for a total of $300. Because the Apparent Money deflated, they have gained over a month’s extra savings compared the price at which Fnord Inc. is selling products during month 3. Subsequently, they each decide to splurge a bit and not save any money.

| Balance Sheet | ||||||

| Month | Apparent Money (per month) | Debt | Fnord Inc. | Jack | Alan | Tina |

| Initial | $3000 | -$1500 | $3000 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 1 | $2400 | -$1350 | $2400 | $150 | $150 | $150 |

| 2 | $1920 | -$960 | $1920 | $270 | $270 | $270 |

| 3 | $1824 | -$736 | $1824 | $270 | $270 | $270 |

While this might seem mighty odd, in Classical Economics this is how the economy is meant to behave. A business is only able to pay as much as it has made, so if all revenue is less than all expenses, expenses need to be cut. Of course, in the real world, the amount of money being passed around doesn’t change by 80% from month to month and of course generally it inflates rather than deflates. When we save our money, in general day, instead of giving us greater power it becomes worth less and less as the money supply inflates. This encourages us to invest our money rather than save it. But as the money supply inflates, our salary itself drops in purchasing power. We need to get a bump in our salary periodically just to stay even. Using the AM measurement to adjust salary, your salary would grow slightly from month to month in a normal, growth economy.

But of course, sometimes the total quantity of purchases through the economy does drop, and at that point businesses have to cut expenses. In Classical Economics, this is handled by lowering wages, but in the real world it’s often handled by cutting employees as has been pointed out in previous blogs.

Increased Savings Equals People Laid Off

After the recession hit, there was a lot of call for banks and other large institutions to be more spendthrifty. One bank, I remember, had a tradition of throwing a big picnic for all of its employees once a year. The average citizen as well as the government all gave evil glares at this bank because of how wasteful they were being in a recession.

In the terms of Classical Economics, this makes some sort of sense. The true state of the economy has become clouded by various people and organizations doing a poor job of managing money, and so money needs to be withdrawn from those so that money can once again be safely spent on things which are financially sound. But in the terms of the real world, this is simply stupid. When the bank doesn’t throw its picnic, the catering company that was depending on the hundreds of thousands of dollars that it had gotten reliably each year for the last decade suddenly can’t pay any of its employees. They have to lay many or all of them off. Unemployment increases, which means that revenue to banks and all other businesses falls further. With decreasing revenue, but wages stuck at high levels by contracts, minimum wage legislation, etc. there’s no way that a business is going to hire on more workers.

Under the AM price adjustment method, however, as the call to save spreads across the nation and revenue starts to be cut across the market place, the cost of maintaining your employees stays consistent with revenue. Everyone is able to continue working and living, holding their money in savings and even having it gain in value the worse things get. When they are certain that measures have been taken to correct what was wrong with the economy to make customer confidence go down, the carrot of the increased purchasing power of their savings kicks in. They can buy a lot at cheap values, so the instant it seems like the air has cleared, people will want to get back into the market.

Of course, there will be some layoffs. The enterprises that were truly wasteful will be cut. But since corporations are saving their money as well, with those savings increasing in value, these laid off people are comparatively cheap to hire back for fiscally sound ventures.

The one interesting point of the AM adjustment is the treatment of loans. In the model laid out in Tying it all Together (Classical Economics), the amount of money paid back in loans is always equivalent to the amount that was loaned. If we continued to track the scenario of Jack, Alan, and Tina, however, the total amount of money paid to the central bank would not equate to the total loaned. To demonstrate, let’s presume that like month 1 and 2 that the AM deflated by 80% each month:

| Balance Sheet | |||||

| Month | Apparent Money | Original Debt (adjusted for AM) | Owed (adjusted for AM) | Remaining Debt (adjusted for AM) Before Payment | Remaining Debt (adjusted for AM) After Payment |

| 1 | 100% | -$200 | $50 | $200 | $150 |

| 2 | 80% | -$160 | $40 | $120 | $80 |

| 3 | 64% | -$128 | $32 | $64 | $32 |

| 4 | 51.2% | -$102.40 | $25.60 | $25.60 | $0 |

Adding the Owed column, the total paid was only $147.60. The AM adjustment scheme creates what I term fundamental money, inflating the economy. Given that all other recession-breaking schemes also create inflation of one sort or the other, this isn’t any particular travesty.

Revisiting Market Bubbles

To revisit the case of Jeff, Tanya, and Berkley that was laid in in Market Bubbles, we’ll show how AM adjustment’s creation of fundamental money solves the standoff created by a collapsing bubble.

1) Tanya borrows $50 from Jeff (the central bank). AM = 100%

2) Tanya buys comic books at above their true value from Berkley for $50. AM = 100%

3) Jeff confiscates comic books and sells them to Berkley for $10. AM = 20%

Since the market has adjusted to the amount that is being spent, down from $50 to $10, the AM has adjusted as well becoming 20%. At 20%, the amount that Tanya owed to Jeff ($50) becomes $10. Tanya has successfully paid off her debt and Jeff considers himself to be fully paid off. He doesn’t have to agonize over tracking down more money. At the same time, the $40 that Berkley has is now worth the equivalent of $200. The bicycle that he wanted to buy cost $120 at old prices. At prices adjusted for the poor economy, it only costs $24. With the $40, he can buy the bicycle that he wanted and go to work at the company that was too far away before.

4) Berkley buys bicycle for $24. AM = 48%

The salary being offered by the time he bicycles over will only be 48% of what it was, but since prices are also 48% of before, that’s perfectly okay. He owes nothing, and since neither Tanya nor Jeff are employed by the business, all of the money that he spent goes back to himself.

5) Berkley receives salary of $24. He spends all of it back on purchases. AM = 48%

If he takes all of his money out of savings and starts spending it, the value of the apparent economy will rise to $40 (80% of the original AM). Until someone goes into debt, it can’t grow any higher than that, so we can say that the market has fully corrected for the bubble. In Classic Economics, it should have corrected all of the way down to $0, but there’s no particular reason that it needs to do that. Ultimately, we left Berkley — who made wise economic decisions — in a pretty position compared to Tanya, who now has nothing. And we did so without stalling the economy.

On the other hand, we let Jeff off easy. He doesn’t have any outstanding debts, so he’s feeling fine to loan again. Of course, he had expected to be able to profit by $20 from Tanya, so in a sense he did lose out. But more importantly, he’s probably not going to loan to anyone trading in comics any more, and really that’s what we want. Ultimately, bubbles will always form and there’s no way to know where they’re going to happen. Plenty of very smart and respected economists thought everything was going fine right up to the moment that the housing crisis broke. You’re better off to fail around it gracefully than to live and breath by “Punish the evildoers!” Figuring out how the bubble happened and making sure it doesn’t happen again is where your attention needs to go. If someone was actually acting nefariously, criminal prosecution is the answer, not trying to milk a stone.

What you will expect to see here are discussions of politics and tangentially economics. This blog will do its best to present a rational look at the world of today, how the modern world came into place, and the issues that are currently being discussed in the public realm.

What you will expect to see here are discussions of politics and tangentially economics. This blog will do its best to present a rational look at the world of today, how the modern world came into place, and the issues that are currently being discussed in the public realm.